By Matthew Thomas in Security | August 27, 2020

In August, Latvia marked the 100th anniversary of the Latvian-Soviet Peace Treaty, otherwise known as the Treaty of Rīga, which ended Latvia’s War for Independence and marked the beginning of the interwar period for the new Latvian Republic. The treaty established Latvia’s sovereignty and Soviet Russia recognized Latvia’s independence as “inviolable” for all time. But the Soviet Union did not honor this treaty, nor its treaties with Estonia and Lithuania. Between these treaties and other, more modern treaties such as the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, we can see that Russia only abides by the treaties it signs for as long as it is convenient, then breaks them when it seems it can get away with doing so.

While the Soviet treaty with Latvia states that the latter’s independence was forever “inviolable,” Russia agreed to “renounce voluntarily forever” its rights to sovereignty in Estonia based on any historical treaty and “unreservedly” recognize Estonia’s right to sovereignty in its own lands. Meanwhile, in the Soviet-Lithuanian treaty, Russia refused to recognize Lithuania as the successor to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, but would recognize Lithuanian independence and most territorial claims on the principle of self-determination.

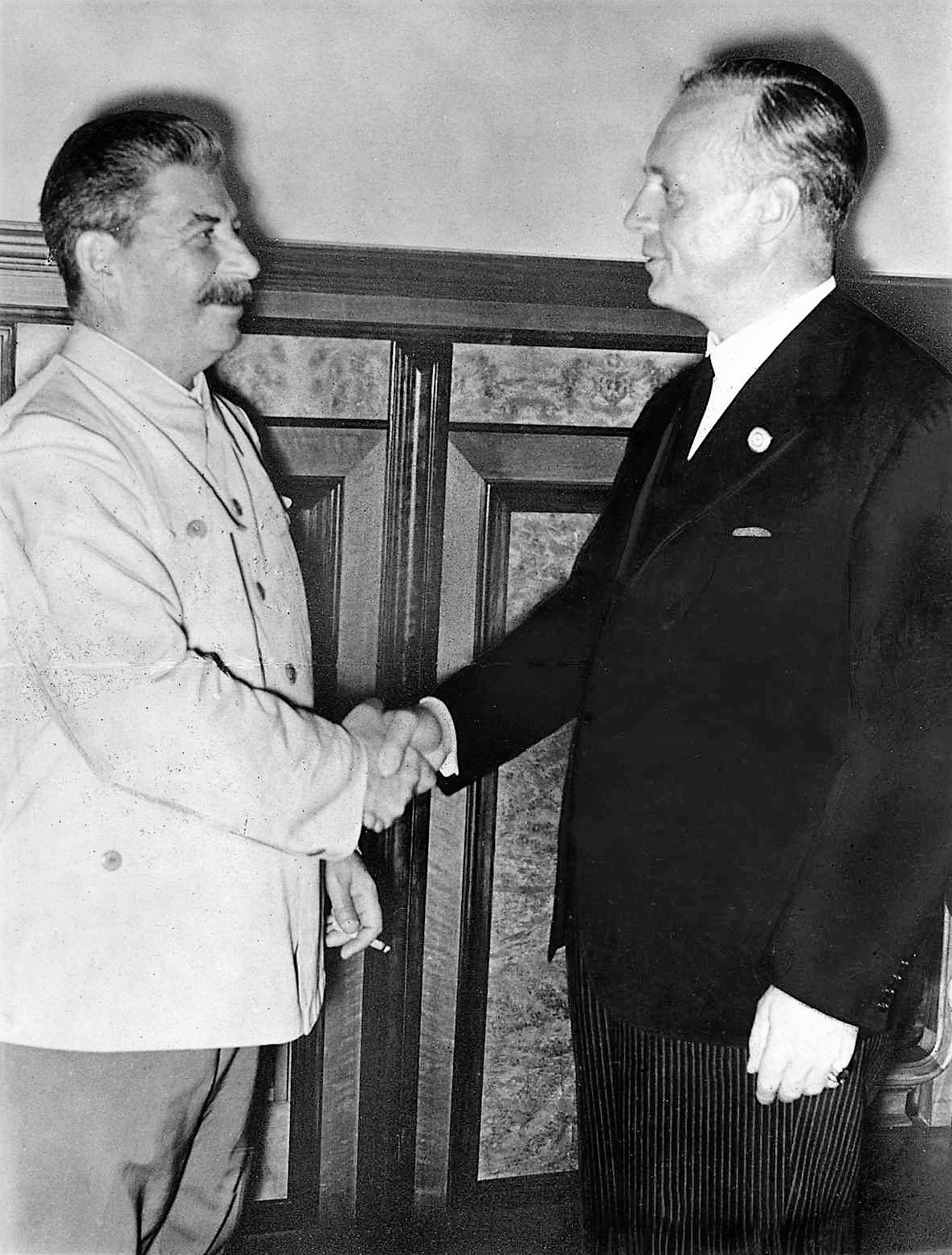

Soviet Russia abandoned all of these principles in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939. Self-determination made way for “spheres of influence,” and ultimately, for the Baltics, annexation. The forever inviolable independence and sovereignty of Latvia and Estonia was only inviolable for about 20 years. Once the Soviet economy had recovered from its devastating civil war, it wanted to take the Baltics back, reneging on its promises to eschew claims to former imperial territory. From 1940-1991, the Baltics suffered under occupation by the Soviet Union (and briefly Nazi Germany in 1941), annexed illegally and against their will.

In more recent history, the United States abrogated the INF Treaty with Russia on the grounds that Russia was not in compliance. Despite the issue being raised more than thirty times prior to abrogation, Russia never showed any intent to get back in line. Rather, it chose to obfuscate its missile tests, accuse the United States of cheating and starting an arms race, and continue pursuing new offensive capabilities prohibited by the treaty. Pundits and politicians alike rushed to condemn the United States’ decision, amplifying Russian propaganda messaging in the process. But, so long as one side is not abiding by the agreed upon terms, and is not making any attempt to get back into compliance, such a treaty provides no security guarantees. At best, it may bring a false comfort, but it would be delusional to suggest it promotes peace.

The hard reality of it is this: Russia and other bad faith actors, such as Iran and China, do not abide by the treaties they sign forever. If they do comply, it is only for so long as it suits them. Then, they will exploit loopholes or brazenly violate their agreements. Further, Russia uses lawfare to create quasi-legal justifications for its actions, redefining the terms of an agreement so as to perpetuate some myth of compliance and Western hypocrisy/aggression. This is not to say that treaties are not worthwhile. They can bring some measure of reassurance, especially if they contain enforcement measures with teeth. They can provide diplomatic leverage, and communicate peaceful intentions. But, in and of themselves, where there is no motivation for an aggressive party to comply, treaties are not a cure-all.

Man has been making treaties since ancient times. A useful illustration of the need for sufficient consequences for treaty violations is found in Genesis chapter 31. In that account, Jacob and Laban made a covenant not to attack one another. Given Laban’s treatment of Jacob earlier in the story, as well as other accounts of his activities, Laban is clearly a scoundrel whose modus operandi is to act in bad faith towards anyone he meets. There is no reason Jacob should have trusted Laban. But, in the ancient world, people made such covenants with God (or gods) as their witness, and they feared the destruction that would befall them should they break their treaty. The only teeth this non-aggression pact had was the witness of God, and Laban was sufficiently afraid of the consequences should he violate his oath. Thus, the treaty was effective. But in modern international relations, a bad faith actor does not necessarily have this fear. Unless Russia (or China, or Iran) expects unacceptable consequences for violating its part of an agreement, there is nothing to stop it from following its habit of breaking treaties. Where there are no repercussions, or where the repercussions are deemed tolerable, man does what he wants. The same is true of governments. A treaty which one side violates while the other side complies can only benefit the violator, if anyone at all. It is at best a placebo, providing some measure of psychological comfort, but no real treatment.

In the context of Baltic security, and security in Eastern Europe writ-large, it would be a mistake to put too much stock in the efficacy of a treaty with Russia. Time and again, Russia has proven itself not to be trustworthy; it seldom keeps promises, and it frequently breaks them. All three Baltic States’ peace treaties with Soviet Russia were broken, and all three suffered under the communist yoke for fifty years of illegal occupation. With no one to stop them, the Soviets brutally took what they had only years before acknowledged was not theirs. And 21st century history tells us that when the opportunity arises, and the consequences are sufficiently tolerable, Russia will seize what it wants. From Crimea to Georgia, Russia has violated the sovereignty of its neighbors with little hesitation and with insufficient consequences.

A well-crafted treaty with sufficient enforcement mechanisms may be useful for a time, but will be hard to achieve and will eventually go the way of INF, ceasing to be effective and needing abrogation or replacement. For NATO, the best bet in Eastern Europe is to pursue diplomatic avenues where possible, but be prepared for the eventual expiration of their efficacy. How can NATO be prepared? By putting forth a strong deterrence posture and a formidable defense. In other words, make the consequences for violation unacceptably costly for Russia.

Cover Photo: Josef Stalin and German Foreign Minister von Ribbentrop at the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Creative Commons. Source: (https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/38/Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-H27337%2C_Moskau%2C_Stalin_und_Ribbentrop_im_Kreml.jpg)