By Matthew Thomas in Policy | October 30, 2020

In 2014, NATO member states agreed to target defense expenditures of two percent of gross domestic product (GDP) by 2024. After this commitment, and following Russian aggression in Ukraine, NATO turned the corner on its declining defense expenditures. Facing a new challenge in a revisionist Russia, many allies to the east felt a new sense of urgency about funding their defense, aiming to build a credible deterrent against aggression on their own territory. Since 2015, NATO defense spending has increased each year on the whole, and this year, two more allies are projected to meet the two percent benchmark. But while this number has been oft discussed and been the subject of much rhetoric, what ultimately matters is not only how much the allies are spending, but how they are spending it. Are member states making wise decisions with their money?

One of the common arguments against using the two percent benchmark for NATO expenditures in defense is that NATO counts all personnel related expenditures, including pensions. Under that accounting system, Greece has consistently met the mark; however, in 2018, Greece spent 75 percent of its defense budget on personnel and pension costs. This argument, and the example of Greece, is usually used to insist that more complacent allies are doing enough with whatever percent they are spending and do not need to get their act together. This is a misuse of the data in question.

Ultimately, members not meeting the threshold they agreed to in 2014 are negligent in failing to do so, as the threat environment in Europe has changed since that time. Likewise, the argument itself is misleading, as it points to an extreme case in Greece among the countries meeting the two percent. Of the seven countries who spent an excess of 60 percent of their defense budgets on personnel this year, only Greece and Croatia are spending above the median 1.86 percent of GDP. Meanwhile, most countries spend the largest percentage of their budgets on personnel – even the United States. Indeed, personnel is a critical component to defense – you cannot expect to win a war with nobody to do the fighting. What truly matters here is both what the allies spend and how they choose to spend it.

Even if a country is investing in the right areas for its defense, if it is not investing enough in those areas, it will be unprepared to fight. Consider the following analogy: Fred and Maureen need to spend 30 percent of their weekly income on groceries in order to have enough food for the week. If they only spend 15 percent of their weekly income on groceries, they will go hungry by Wednesday even if they spent that 15 percent on a balanced diet. So member states can pat themselves on the back all they want for purchasing some necessary weapons system, for example, but in time of crisis, if they do not have enough of these armaments, the purchase is meaningless. They will still be deficient in that capability, and they will lose on the battlefield.

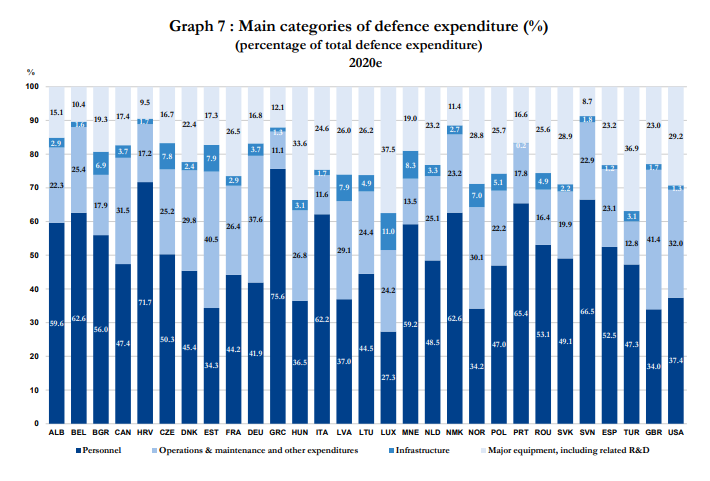

In 2020, ten NATO members are projected to reach the two percent benchmark. These are: The United States, Greece, the United Kingdom, Romania, Estonia, Latvia, Poland, Lithuania, and newcomers France and Norway. Of these, Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Romania have national laws and agreements to meet two percent of GDP on defense expenditures annually. Both politically and geographically, this comes as no surprise – these are some of the most vocal members about the seriousness of the Russian threat. But how are these allies spending their defense budgets? The following graph from the October 21, 2020 NATO communique on defense spending breaks down how each of the allies is spending its money:

Source: Source: NATO.org, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2013-2020).” Communique. 21 October 2020. Pg. 5.

Source: Source: NATO.org, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2013-2020).” Communique. 21 October 2020. Pg. 5.

Among the Baltic States, Lithuania spends the most on personnel (44.5 percent), followed by Latvia (37.0 percent), and Estonia (34.3 percent). It is reasonable that Latvia is in the middle here: it does not rely on conscription, so it has a smaller personnel component; but, in order to maintain a fully professional military, it must spend enough on its soldiers, sailors, and airmen to make the military a viable career. In operations, maintenance, and other related expenditures, the results are reversed; Estonia leads this time (40.5 percent), Latvia remains in the middle (29.1 percent), and Lithuania follows (24.4 percent). This too is no surprise: Estonia has hosted numerous military exercises this year, and the Estonian conscripts continued to train (safely) in spite of the COVID-19 pandemic. Most of the allies (all except Luxembourg) are spending less than 10 percent of their defense budgets on infrastructure. Here, the Baltic States are among those spending above the average. Latvia and Estonia are both spending 7.9 percent of their defense budgets on infrastructure, while Lithuania is spending closer to (but still well above) the median value at 4.9 percent. This can largely be explained by improvements to the aging and largely inadequate transport infrastructure in the Baltic States, as well as investments in critical energy and communications infrastructure and in Host Nation Support capabilities. On equipment procurements and research and development (R&D), Lithuania and Latvia are spending nearly identical percentages (26.2 and 26.0 respectively), and Estonia is spending 17.3 percent in that area. For Lithuania and Latvia, this represents a considerable increase over the past six years, and a modest, but still considerable drop for Estonia during that time. Yet context is necessary here: for many years, Estonia has been consistent in its procurements, while Lithuania and Latvia have been playing catch up since 2014.

In the Baltic context, these percentages provide insight into each state’s priorities. Estonia has less need to invest in weapons systems and other equipment procurements: it has been consistent in that area already and is ahead of its peers, though improvements in that category remain important. Instead, it has greater need of infrastructural improvements (indeed, fixing bridges was part of Estonia’s training routine this year), particularly with regard to transportation logistics. Meanwhile, Estonia’s focus on preparedness clearly explains why it leads (by far) on operational expenditures.

Latvia, on the other hand, has had to play catch up on procurements, and has done so rapidly. That said, the focus has primarily been on land based deterrence, so there remain critical weaknesses in the air and maritime domains. The same rings true in Estonia and Lithuania. For Latvia, training is important, but since it maintains a fully professional military, it does not need to spend as much as Estonia (or really, Lithuania) on organizing and implementing training events. To a large degree, it is Latvia’s policy of maintaining a fully professional military, rather than relying on conscription, that puts it firmly in the middle of its neighbors in both operations and personnel. Lastly, on infrastructure, Latvia faces similar problems to Estonia: the road and rail networks are inadequate for the logistical needs of war, Host Nation Support capabilities need continued improvement, and critical energy and communications infrastructure need greater security.

Lithuania, like Latvia, has made quick work of procuring necessary equipment and weapons systems over the past six years to fill in critical gaps in its defensive posture. Lithuania spends the most on personnel, which is reasonable considering it has the largest population among the Baltics (by a considerable margin) and relies on conscription. Estonia, which also relies on conscription, has the smallest population. It is interesting that Lithuania spends the least among its Baltic peers on operations and infrastructure. On infrastructure, it is reasonable to say that Lithuania was ahead of its peers in making improvements, but much more work remains in developing its highway and rail systems, as well as securing critical energy and communications infrastructure and improving Host Nation Support. It is not surprising that Lithuania spends less here, but perhaps that it spends as little as it does. Regarding operations, expenditures are fairly comparable with Latvia’s, and the difference between it and its neighbors this year may be reflected in part by its COVID-19 policies in addition to more typical factors, such as logistical expenditures for say, fuel.

For each country, a national security strategy, or at minimum some coherence on defense policy, is crucial for budgeting defense expenditures. After 2014, the two percent threshold is critical – not only does this reflect a deteriorating security situation in the east vis-à-vis Russia (and now Belarus), but if members do not abide by it, their negligence will amount to clear unreliability. They clearly seen as all talk and no action. How they spend that two percent, however, is even more important. Procurements should be economized to maximize their added value and make room for other needed equipment and armaments. Spending on infrastructure should reflect the needs of each country, both in the Baltic context and in NATO as a whole. Each should be done responsibly, minimizing waste, fraud, and abuse. This can only be achieved when policy is coherent and strategic. Likewise, training and operations budgeting should reflect the needs of each country and should be done based on critical weaknesses and priorities identified in the context of realistic scenarios. Finally, spending on personnel should be adequate for maintaining a capable and motivated military force, without being done irresponsibly. In the Baltic context, a regional security strategy may be helpful to help Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania make joint procurements to maximize added value and achieve outsized results compared with their limited resources. Likewise, it will help identify common areas for training needs and infrastructural improvements, particularly with regard to military logistics, a crucial regional weakness.

When push comes to shove, military preparedness should not be a politically divisive issue. All countries should seek to be as well prepared to defend the homeland as they can possibly be, even in the context of collective security within NATO. Within that, they should be prudent with their money, investing enough to meet or exceed their needs, maximizing the added value of their investments, and demonstrating to its foes that NATO is credible. For small countries, like the Baltic States, NATO’s credibility is key: without the resources on their own to defeat or even adequately deter Russia, they need NATO to stand tall. And it is for this reason that what other allies spend on defense, and how they spend it, matters for the Baltics.

Cover Photo: Flags of member states outside NATO Headquarters in Brussels. Creative Commons