By Matthew Thomas in Security | February 27, 2020

At the end of last month, Lithuania and Poland announced that the two countries would each assign a brigade to NATO Headquarters in Poland to “train and act together” for the defense of the Suwałki Gap. According to the signed act of affiliation, Lithuania’s Iron Wolf Mechanized Brigade and Poland’s 15th Mechanized Brigade will train jointly to prepare for operations in the Gap, though they will remain under their own national command. The framework for this cooperation has its origins just over a year ago with the creation of the Polish-Lithuanian Defense Council, and this is its first concrete act. This agreement will allow for greater cooperation on defense and security related matters, such as coordination of defense plans and joint exercises. Grand comparisons to 15th and 16th Century battles against the Teutonic Order and the Grand Duchy of Moscow and even to the Cold War era Fulda Gap aside, this new development in Polish-Lithuanian cooperation is quite welcome in a region widely considered to be a weak spot for NATO.

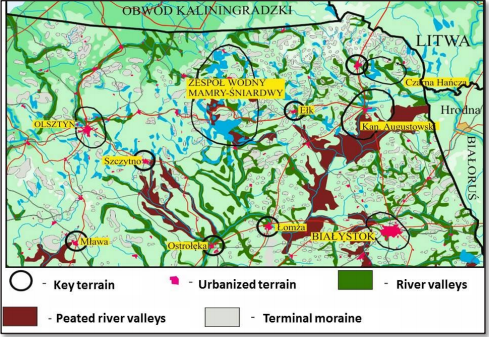

The Suwałki Gap is the narrow Polish-Lithuanian border region sandwiched between Russia’s Kaliningrad exclave and Belarus. This area is of critical logistical importance to NATO, seeing as it is the only land border between the three Baltic States and the rest of the alliance. Presently, it contains only two minor highways running in a general north-south direction, as well as some smaller local roads and roads used by the logging industry and forest services. As such, it could serve as a tactical chokepoint, wherein Russian forces could stymie troop and supply movements north. Maintaining control over the Suwałki Gap, therefore, is critical in the event of war in the Baltic Theater with Russia.

The Suwałki region, however, presents major advantages for defense and significant obstacles for offensive operations. If NATO can deny Russia access, it will be that much more difficult for Russian troops to launch an offensive campaign there. If, on the other hand, NATO does not deny Russia access, and Russia gains control in the region, it will be extraordinarily difficult for NATO to reopen the critical corridor from Suwałki to Kaunas in order to supply operations in the Baltics.

The terrain is heavily forested and hilly, and is dotted with lakes, rivers, and marshes. Forests and lakes comprise approximately 50 percent of the land area, while swamps form another 11 percent. The hills run latitudinally and are intersected by rivers and lakes. Moraine dammed lakes are generally shallow, widely dispersed, and have soft embankments, while step, high banks and irregular bottoms characterize local ribbon lakes. Rivers in the region flow northward, and are generally narrow and winding, with steep and heavily forested banks. Many of the coniferous forests in the region are practically impassible, and most are inaccessible (or at least foolhardy) terrain. Clay and sandy clay soils in the region make for impassible conditions in rainy weather with deep, dense, and soggy mud. And indeed, rainy weather is typical for much of the year from the spring thaws all the way to autumn. In the wintertime, snow and frost inhibit movement. Snow covers the ground an average of 90 days per year, heavy frost an average of 50 days, and 30 days see ground frost temperatures. Soils are frozen approximately 120 centimeters deep in the winter, but frozen lakes and rivers may be crossable. Furthermore, the limited road system in the region is poor, and many bridges can only sustain a weight of about 50 tons, which will support a Russian tank, but not an American or British tank, as these average about 70 tons. Though there are pontoon bridges, these are few in number and not suitable for the local rivers. Besides weight limitations, these roads will not sustain movements of larger military vehicles in formation, meaning such equipment would either be forced to find alternate routes or would be “canalized” into long, slow lines or short caravans with limited numbers, nullifying any numerical advantage offensive forces might have.

Map of the Suwałki region and its physical characteristics. Source: Col. Leszek Elak and Col. Śliwa, Zdzisław (ret.) “The Suwałki Gap – NATO’s Fragile Hotspot,” published in Zeszyty Naukowe AON nr 2. (103), 2016.

Map of the Suwałki region and its physical characteristics. Source: Col. Leszek Elak and Col. Śliwa, Zdzisław (ret.) “The Suwałki Gap – NATO’s Fragile Hotspot,” published in Zeszyty Naukowe AON nr 2. (103), 2016.

The regional terrain and climate are atypical, and local operations will require specialized training and equipment. These conditions readily benefit defensive operations by creating natural defensive lines and allowing armies to restrict movement with limited force, especially if road infrastructure is destroyed. Defenders in the region can further limit maneuverability in a number of ways, including creating engineering obstacles, developing camouflage and deception components to inhibit air and land reconnaissance, and establishing combat support and combat service assets locally. Further, the terrain itself limits the ability to reorganize combat units and restricts logistical support to react to changes in the tactical situation. On the other hand, the terrain supports covert operations. As a result of limited lines of sight and likely robust covert scouting operations, artillery is also limited in its usefulness for offensive operations in the Suwałki region.

Typical forest wetland landscape near Augustów. Source: augustow.pl

Typical forest wetland landscape near Augustów. Source: augustow.pl

Two key considerations must be brought up here: first, NATO can gain a serious tactical advantage by investing in early warning capabilities, surveillance and reconnaissance capabilities, and facilitating information sharing in the region; second, Russia cannot close the Suwałki Gap without involving Belarus somehow. Regarding the first, it is blatantly obvious that NATO can better secure the region by investing in capabilities which enhance situational awareness, but the result of that investment is the key here: greater awareness allows greater time to surge forces into the theater, putting NATO in position to take advantage of a defensive posture in a local environment wholly suited for defense. The second is a little less obvious, as Kaliningrad is itself heavily militarized, while Belarus is less so. But, in order to effectively close the Suwałki Gap, Russia must deploy missiles over or from Belarus, or must deploy troops through Belarus, or less likely, coerce Belarus into joining the fight. Otherwise, a Belarusian route around the Gap remains open in a conventional war scenario. Such moves would escalate the situation to a point where strikes on Kaliningrad, Russian forces in Belarus, or even to the main part of Russia itself would be justified. Belarus, especially as relations currently stand, will be reasonably reluctant to allow any of the above scenarios, and NATO forces could theoretically hold local Russian assets at risk, turning the anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) balance in the region on its head against Moscow.

The Suwałki Gap presents both strategic challenges and strategic opportunities. If NATO can secure the Gap, it can maintain the vital overland supply line from Poland to the Baltics. Further, it can use the Gap to hamper Russian activities and capabilities around Kaliningrad and Belarus. From Polish acquisition of F-35 jets and Lithuanian acquisition of Joint Light Tactical Vehicles (JLTVs), to cooperation on the joint Polish-Lithuanian brigade to defend the Suwałki Gap, we have seen many positive measures for improving regional defense. But there is certainly more work to be done. It would be reasonable to expand the number of joint brigades; one probably is not enough. Secondly, infrastructural improvements are needed to ensure NATO tanks can cross bridges safely. NATO should invest in air defense and surveillance systems, and should seek to improve situational awareness locally in the Suwałki region. Finally, NATO needs to train and prepare for operations in the unique conditions the terrain, soil, climate, and infrastructure provide in order to improve overall readiness. As the only land route between the Baltics and the rest of NATO, this small piece of territory bears outsized significance for military operations in the Baltic theater. NATO must maintain it.

Cover photo: NATO exercises in the Suwalki Gap Region. Published by NATO. Creative Commons. Credit

Sources:

Col. Leszek Elak and Col. Śliwa, Zdzisław, “The Suwałki Gap – NATO’s Fragile Hotspot,” Zeszyty Naukowe AON, nr 2 (103), 2016.

Globalsecurity.org, “Suwałki Gap,” https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/europe/suwalki-gap.htm

Michael A. Hunzeker and Lanoszka, Alexander, “Threading the Needle Through the Suwałki Gap,” EastWest Institute, 26 March 2019. https://www.eastwest.ngo/idea/threading-needle-through-suwa%C5%82ki-gap

LRT English, “Poland and Lithuania to plan joint Suwałki Gap defence,” 29 January 2020. https://www.lrt.lt/en/news-in-english/19/1137647/poland-and-lithuania-to-plan-joint-suwalki-gap-defence

Viljar Veebel and Col. Śliwa, Zdzisław, “The Suwałki Gap, Kaliningrad and Russia’s Baltic Ambitions,” Scandinavian Journal of Military Studies, 21 August 2019. https://sjms.nu/articles/10.31374/sjms.21/